Father Roger Guindon: man of many talents

On November 17, the entire university community was plunged into grief by very sad news—Father Roger Guindon, the clergyman of deeply held beliefs, had died at 92. Considered the founding father of the university as we know it today, Father Guindon was good-natured, humble and fiercely intelligent. He made a difference by laying the foundation for a world-class institution.

Whether they knew him up close or from afar, Father Guindon’s friends, loved ones, peers and colleagues all agree: they will be marked forever by this straight-shooting man with a colourful, direct manner. Moreover, none failed to be touched by his legendary sense of humour. His jokes could make you burst into laughter and get you thinking at the same time. Often, though, they were just to make those in his circle blush!

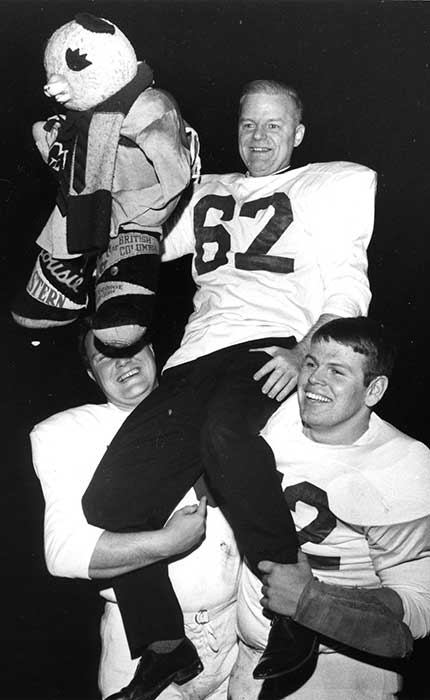

The rector loved sports and regularly attended the University of Ottawa Gee-Gees’ football games. Credit: Dominion-Wide Photographs

“He was a very nice person,” Marcel Hamelin, dean of the Faculty of Arts under Father Guindon and later rector himself, recalls. “He got your attention through his expressive vocabulary, and when he wanted to get a serious message across, he preferred to tell a story rather than preach.”

Physically imposing, Father Guindon had a natural presence about him. He was in his element no matter where he was. “He was just as comfortable with prime ministers as with the most humble of people,” recounts Pierre Garneau, longtime friend of the Oblate father. “He was a very humble man who knew how to put people at ease.”

In 1972, Father Roger Guindon was named a Companion of the Order of Canada. Credit: University of Ottawa Archives

Even though Father Guindon had many friends in high places, he remained a very simple man. “It was disarming,” recounts Hamelin. “He wasn’t attached to money or material goods at all. He also enjoyed saying that when a meal cost him more than 12 dollars, it gave him indigestion!”

He had very close family ties. As well, two of his uncles, Arcade Guindon and Auguste Morisset, were a big influence on him. At one time, all three worked at the university, until his uncles retired in the 70s. “The two uncles were warm, down to earth people. They were also very close to students at the university,” says Martin Laplante, a nephew of Roger Guindon’s.

His fellow members of the clergy and the university were part of his extended family. “He saw himself as the father of the university,” observes Father Pierre Hurtubise, former Saint Paul University rector and Oblate colleague of Father Guindon.

Modest origins

Those who knew Father Guindon invariably describe him as quick-witted, intelligent, funny and charming. Credit: University of Ottawa Archives

Born in 1920 in Ville-Marie, an Oblate parish in Témiscamingue, Roger Guindon was the oldest of five children. His father was an accountant and his mother a teacher. His paternal grandfather was a farmer in Clarence Creek, in Eastern Ontario. Despite their modest beginnings, almost all his siblings studied at the University of Ottawa.

Roger Guindon himself first arrived at the university as a 13 year old in 1933. He maintained ties to this institution for 70 years, and remained active here even after his term as rector ended in 1984.

Father Guindon holds the record for the longest unbroken term as rector (now president) in the history of the University of Ottawa. “He was the leading rector of the twentieth century at the university,” says Michel Prévost, university chief archivist and longtime friend of Father Guindon. “Under his administration, the campus underwent its greatest development, with fifteen or so buildings being built. During the 1970s, the university grounds were like a permanent construction site.”

Father Guindon truly dedicated his life to the university. “In a speech he gave some years after his retirement, he said, ‘I left the University of Ottawa in 1984, but the university never left me,’” recounts Father Hurtubise.

A natural negotiator

Before being named rector in 1964, Father Guindon taught moral theology for fifteen years. Unbeknownst to him, he was preparing for the role he would one day have at the University of Ottawa. He often said that being a moralist was a big help to him in his work as rector. “It gave him both a framework and a certain flexibility in his negotiations with people. Basically, he respected everyone’s opinions, even when he disagreed,” emphasizes Father Hurtubise.

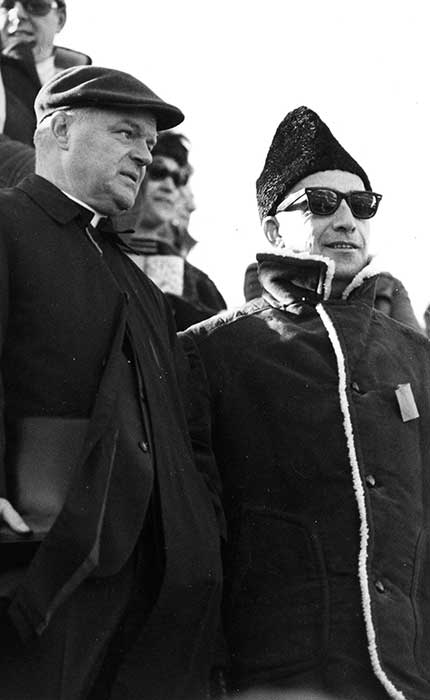

Father Guindon and Carleton University rector Davidson Dunton during a football game between the Gee-Gees and Ravens in 1969. Credit: D.A. Gillmore

He was a skilled negotiator, especially in his dealings with the Ontario government. This is what allowed him to carry out a major transformation of the university, from a private Oblate school to a public institute of higher learning.

“He knew how to use his clerical collar to advance his cause,” says lawyer Mark E. Turcot, president of the Student Federation of the University of Ottawa from 1973 to 1974. “He was a very persuasive man. You couldn’t sleep well if you said no to him. You might as well give in!”

An approachable rector

Like the father of a family, Roger Guindon was always available. His door was wide open for students who wanted to talk to him.

Father Roger Guindon was one of the University of Ottawa Gee-Gees’ most dedicated fans! Credit: University of Ottawa Communications Service

But even though he was so approachable, he could sometimes be very tough when negotiating with students. “I cut my teeth with him,” recalls Turcot. “With Father Guindon, you had to always arrive well-prepared. Our discussions were sometimes stormy, but despite everything, he never held a grudge.”

“At first, my relationship with Father Guindon was tense,” recalls federal MP Mauril Bélanger, president of the Student Federation from 1977 to 1979. “But I soon saw that he was very good man, fair and accessible. With him, the role of the Student Federation on campus grew, because he encouraged student initiative.”

The rector also encouraged dialogue with students. So much so that in 1976, he agreed to take part in a debate organized by the Student Federation on a proposed hundred dollar tuition increase. “The opposition was mobilized and he was strongly attacked,” remembers Lucinda Annette Landau, vice-president of the federation from 1977 to 1978. “He finally managed to get all the students to understand that the increase was essential, since tuition hadn’t been increased in five years.”

A champion of bilingualism

Roger Guindon’s father, Aldéric Guindon, was from Vankleek Hill, in Eastern Ontario, while his mother, Germaine Morisset, was a Franco-American from Fall River, Massachusetts. His parents both coming from Francophone minority settings may explain in part Father Guindon’s dedication to the cause of bilingualism.

“Expanding programs in French at the university was a constant concern for him,” mentions Hamelin. “Thanks to his determination, common law is taught in French at the university and there is medicine program in French.”

Father Roger Guindon in the company of Chancellor Pauline Vanier (left) and Barbara Ward (Lady Jackson) during the 1967 Convocation ceremony. Credit: Studio C. Marcil

Father Guindon liked to say that the University of Ottawa was a university unlike any other. He saw it as a meeting point of two intellectual traditions, Francophone and Anglo-Saxon. “For him, it was a school of tolerance where you learned to appreciate difference,” says Hamelin.

Some would say that if Father Guindon hadn’t been head of the University of Ottawa at the time, the major changes it experienced could not have taken place. “Who else could have negotiated with the minister of education at the time?” asks Senator Hugh Segal, president of the Student Federation from 1970 to 1971. “Bill Davis came from an Anglo-Protestant background and knew little about Francophone culture. Father Guindon was the only one able to win him over to the cause of bilingualism, which allowed the University of Ottawa to become a one-of-a-kind institution,” concludes Segal.

![]()

Father Guindon had a keen sense of humour. Students were all ears when he told his hilarious stories. Credit: University of Ottawa Archives